If you have a Twitter problem like I do, you’ve probably been hearing way too much about Robert Kennedy Jr. these days. If not, here’s a quick summary for you:

Years ago, he started out believing all the conspiracy theories about who killed his relatives, which were almost certainly wrong, but harmless enough. Then he became an anti-vaxxer. Since he decided to run for president, (seemingly a dangerous choice if he honestly believes there’s a conspiracy to murder every Kennedy who attains high office, but I digress) he’s started mixing every conspiracy theory and pseudoscience under the sun, and throwing in some random made-up facts for good measure, like a sort of Bullshit Voltron.

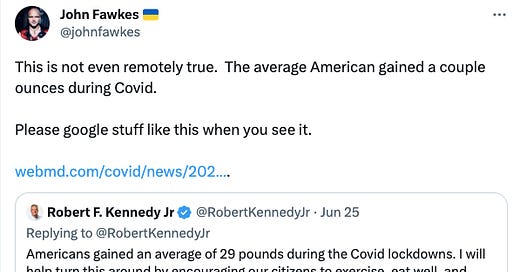

Anyway, here’s the source he was citing. The volunteers at Twitter community notes already got started on explaining how Kennedy was mischaracterizing the survey: 29 pounds was the average self-reported weight gain among the 42% of Americans who reported unwanted weight gain, not the average weight change among all Americans.

Now this is a legit survey by the APA, a highly reputable source, but it’s never a good sign when you check someone’s source and within ten seconds can tell they were citing it inaccurately. For anyone who isn’t clear on this, there are two issues with this survey– leaving aside the fact that it doesn’t even try to answer the question of how much the weight of the average American changed.

First, the survey asked people about undesired weight change. The “undesired” part is doing a lot of heavy lifting here; as you might imagine, weight gain, whether planned or not, is more likely to be seen as undesired than weight loss.

Second, this is all self-reported data. Self-reported data has a lot of problems, to say the least, why is why studies try to use objective measurements when they can. And when it comes to people’s weight, of course they can– patients get weighed when they visit the doctor!

So here’s the study I cited on Twitter. It looked at data from over 100,000 adults who were treated at the University of Pittsburg during the pandemic, which means I admittedly made a mistake in citing it too– this is data from one metro area and I shouldn’t have said it represented the whole country.

Anyway, it found that the average patient gained 1.4 ounces from March 2020 to November 2021, a period of 20 months. For comparison, patients at the same hospital (not all the same people, but mostly) gained .4 pounds from January 2018 to March 2020, a 22-month period. In other words, they actually gained weight during the pandemic at about half the rate they had before!

But again, that’s just Pittsburg, and I should have looked for a better source before I tweeted. So I’ll rectify that now.

An analysis of anonymized weight data from 15 million Americans shows that the average American gained less than one pound during the first year of the pandemic. Of course there’s a lot of individual variation, with some people gaining or losing more than 30 pounds. But then, there always is, which is why the researchers compared this to what happened during a similar period before the pandemic.

As you can see, there is a small but clear trend towards more weight gain during the pandemic than before.

The research team then went further by looking at the longer-term trend in the body weight of American patients.

As you can see, the average body weight has tended to rise by about .7 pounds a year since 2017. It would honestly have been better if they’d looked a few years further back to establish that trend line, but in any case, when you account for that, the U.S. is only half a pound above trend.

Note that this comes from a larger sample of 50 million patients, since they didn’t need to limit themselves to using patients who were weighed during all four of the study periods they used for the previous chart.

This is an extremely well-designed study, and I applaud the people at Epic Research for conducting it.

It’s also very surprising. Honestly, when I googled how much weight Americans had gained during the pandemic, I expected the answer to be five pounds or so, and I suspect most people would have as well.

A few theories on (lack of) weight gain during covid

The first explanation– and one that definitely applies to most people to some extent– is that that plenty of people kept going in to work. Roughly a third of Americans either didn’t work from home, or didn’t do so exclusively for more than a few months.

Second, the word “lockdown” got overused a lot, but it’s not as if we were all locked in our homes. People still went for walks, went hiking and so on– at its worst, we had to avoid large gatherings and a lot of indoor activities.

While many people were afraid to even go for a walk in non-crowded areas, many others took up the opportunity to find new outdoor activities. I took up photography, and one of the models I met through my photography said she started modeling during Covid to replace her old hobby of mixed martial arts. It takes all kinds.

Third, the inability to eat out forced people to eat more home-cooked food. On balance this is a good thing, which is why trainers, dietitians, health coaches and so forth are always harping on people to cook more. Cooking makes you fully aware of what you’re eating, and home-cooked food is fairly consistently healthier than fast food and stuff from bakeries, coffee shops, and low-end eateries.

Fourth, covid killed our social lives, which sucked. But that goes hand in hand with the no eating out, and for most people it meant sleeping on a more regular schedule, which is healthy.

It didn’t kill alcohol sales however– they actually went up significantly, as did alcohol-related accidents and hospital visits. Americans self-report less alcohol consumption, but that is contradicted by the alcohol industry’s own sales figures. See what I mean about self-reported data being unreliable?

Fifth, maybe people lost muscle but gained fat and it mostly evened out. This is probably true for many of the 30% or so of Americans who resistance train at least twice a week. It depends on how they train– if they were working out at home maybe they actually trained more, but for most people who lift heavy weights at the gym– like me– covid definitely resulted in a bit of muscle loss and concurrent fat gain.

All five of these explanations are true to some extent, but which one predominated depending on who you were and what you did during the pandemic. If you cooked more– great! If you hiked more– great! If you lifted less and didn’t replace that with other activities, or spent more time drinking at home– not so good.

Surprising data is always open to multiple interpretations, and it’s important to spend time to come up with multiple explanations. If you only have one explanation for something, you’ll be heavily biased towards believing it’s true just because it’s the only one you have.

But if there’s one thing you should take away from this, it’s that you should immediately google everything you hear to see if it’s true. In fact, you should do this even for things that sound like they’re probably true (sometimes the truth is surprising) and even if they come from a much more reputable source than Bobby Kennedy.