Should you put raw eggs in your protein shakes? Does cooking meat denature the protein?

I’m a big fan of protein shakes. Well, I don’t love them. I love the results they get me when I’m bulking. I used to put raw eggs in my protein shakes. I’ve since stopped, but maybe not for the reason you’d think.

You may not know this if you’re not involved in the health foods “community,” such as it is, but a lot of people really don’t think you should cook your food. Or at least, they don’t think you should cook protein-heavy foods.

There are a few lines of argument behind this idea:

Humans evolved to eat raw food. That’s food’s natural form after all, and we haven’t evolved to eat cooked food.

Cooking your food- and specifically meat- creates toxic chemicals that cause cancer.

Cooking denatures the proteins in your food, making them less nutritious and bioavailable, if not indigestible or even outright toxic.

As crazy as eating raw food may sound, it’s important to note that all three of these are at least partly true- people obviously evolved eating raw foods up until a certain point, overcooking your food has been shown to produce toxic byproducts sometimes, and cooking does denature the proteins in your food.

So does that mean you should stop cooking your steak? Well, not so fast. If you’ve been paying attention, you should have a few big questions on your mind right now.

What a damned minute. What does “denature” actually mean?

Good question, hypothetical readers. Meriam-Webster’s dictionary defines it thusly:

: to deprive of natural qualities : change the nature of: such as

a : to make (alcohol) unfit for drinking (as by adding an obnoxious substance) without impairing usefulness for other purposes

b : to modify the molecular structure of (something, such as a protein or DNA) especially by heat, acid, alkali, or ultraviolet radiation so as to destroy or diminish some of the original properties and especially the specific biological activity

We’re obviously dealing with definition b here- denaturing protein destroys or diminishes some of its existing natural properties. And if you read any articles about this on raw foods websites, they tend to quote this definition as proof that proteins are healthier when left uncooked.

There’s a famous segment from The Man Show in which Adam Carolla and Jimmy Kimmel set up a booth at a farmer’s market and urge people to sign a petition to end women’s suffrage. Almost everyone who comes to their booth signs it.

The people who sign the petition do so not because they don’t want women to vote, but because they have no idea what suffrage means, and instead of asking someone or looking it up, they guess that it must mean suffering. Because that sounds about right, doesn’t it?

The segment is a reminder- simultaneously hilarious and depressing- of both the sorry state of political education in America, and the dangers of assuming you know more than you do. So back to denaturing. The word just sounds bad. And admittedly, the definition isn’t helping any- who wants to destroy or reduce the natural properties of delicious, nutritious protein?

Except, uh, which properties are we talking about here? What specifically is happening on a molecular level when protein gets denatured? Most raw foodies won’t go into that level of detail, but I will.

Proteins are made of amino acids, and they have either three or four levels of structure by which those amino acids are arranged.

First there’s the primary structure, which is simply a linear sequence of amino acids joined by peptide bonds. So the primary structure might be gluatmine-alanine-valine-leucine-glutamine-arginine, for instance. This primary structure can be thousands of amino acids long, but it’s still just a straight chain of amino acids.

Then there’s the secondary structure, where the primary structure is folded, bent and twisted, forming a three-dimensional shape. Typical secondary structures include a coil, pleated sheet, or single helix. Once the protein starts bending like this, some of the amino acids also start to form side-chain bonds, so the structure also gets more complex than just a straight sequence of amino acids.

After the secondary structure there’s a tertiary structure, which is created by joining two or more secondary structures together. For instance, when two helix structures attach together they form- say it with me- DNA.

Some proteins also have a quaternary structure, formed by multiple tertiary structures being joined together by interacting polypeptide chains, forming an oligomer.

So what does denaturation mean as it applies to protein specifically? It refers to the breakdown of these structures. Denaturation breaks down quaternary structures into their component tertiary structures, tertiary into secondary structures, secondary into primary structures, and finally breaks down those peptide chains into individual amino acids.

At this point you can probably guess what I’m about to say next: protein denaturation happens naturally, as a part of the digestive process. Specifically, the hydrochloric acid in your stomach breaks down the quaternary, tertiary and secondary structures, and pepsin in the stomach breaks down some of the interior peptide bonds within proteins.

What makes it out of the stomach are mainly primary structures, which are broken down in the intestine by the enzymes trypsin and chymotrypsin. The end products of digestion are mostly free amino acids and very short primary structures, usually dipeptides and tripeptides- sequences of two or three amino acids.

And that’s the way it should be, as absorbing whole proteins into your body could cause problems. If intact beef DNA made it into your bloodstream for instance, it would trigger an immune reaction- or if your body didn’t destroy it, that beef DNA would start creating RNA and sending out commands to the rest of your body, doing its best to turn you into a cow.

So yeah, cooking denatures the proteins in your food. But as you can see, that needs to happen anyway, so cooking really just gives you a head start on the digestion process, making it quicker and easier, and reducing the likelihood that your body will fail to fully digest your food.

But didn’t we evolve to eat raw food?

I mean, originally, sure. The real question here is whether we’ve had fire for a sufficiently long time to have evolved to subsist on cooked food.

Now obviously, fire is one of the first technologies people ever developed. But just how long ago did our ancestors start using it? Twenty thousand years ago? Fifty thousand?

Here’s what the Wikipedia article on human control of fire has to say:

Claims for the earliest definitive evidence of control of fire by a member of Homo range from 1.7 to 0.2 million years ago (Mya). Evidence for the controlled use of fire by Homo erectus, beginning some 600,000 years ago, has wide scholarly support. Flint blades burned in fires roughly 300,000 years ago were found near fossils of early but not entirely modern Homo sapiens in Morocco. Evidence of widespread control of fire by anatomically modern humans dates to approximately 125,000 years ago.

So it turns out that cooking is…actually older than the human race as we know it. Turns out it was invented by the species before us.

And that doesn’t even address the question of whether raw meat was ever superior to begin with. The fact that we ever started eating cooked meat suggests that it had advantages right from the start. Killing bacteria and parasites most obviously, and allowing us to eat slightly less-fresh meat, but the denaturing of the protein was probably also a positive factor from the first day a caveman tried eating seared mammoth.

There’s also evidence that we’ve evolved to use fire in other ways besides our digestion. Most notable is the evidence that we’ve evolved to rely on fire as a light source. Despite our lack of natural night vision, we sleep only 8 hours a night, and this number varies very little with the seasons, whereas most diurnal animals have evolved to wake up and dawn and go to bed at sunset. In other words, we naturally stay up at night.

Bottom line: we’ve had fire for hundreds of thousands of years, and we evolved to rely on it well before the dawn of recorded history.

That’s cool- but what do studies say about my raw egg protein shakes?

Well, they can give you salmonella, although the risk isn’t nearly as high as most people think. That’s not why I stopped consuming raw eggs though.

The reason I stopped is because cooked protein is just so, so much better for you. Twice as good, in fact- one lab study found that cooked eggs provide twice as much digestible protein as raw eggs.

So you could put raw eggs into your protein shakes, and you’ll probably be alright- I’ve had hundreds of them and never gotten sick. But it might give you diarrhea from all the undigested food passing through you, and it’s simply a waste. Better to leave out the eggs, add in an extra scoop of whey/casein blend, and save the eggs for breakfast.

So there’s your answer for eggs- what about meat? A 2012 study by Bax et al on the effects of cooking, aging and mincing on the digestion of pork protein found the following:

Under our experimental conditions, aging and mincing had little impact on protein digestion. Heat treatments had different temperature-dependent effects on the meat protein digestion rate and degradation potential. At 70 °C (160 °F), the proteins underwent denaturation that enhanced the speed of pepsin digestion by increasing enzyme accessibility to protein cleavage sites. Above 100 °C (212 °F), oxidation-related protein aggregation slowed pepsin digestion but improved meat protein overall digestibility.

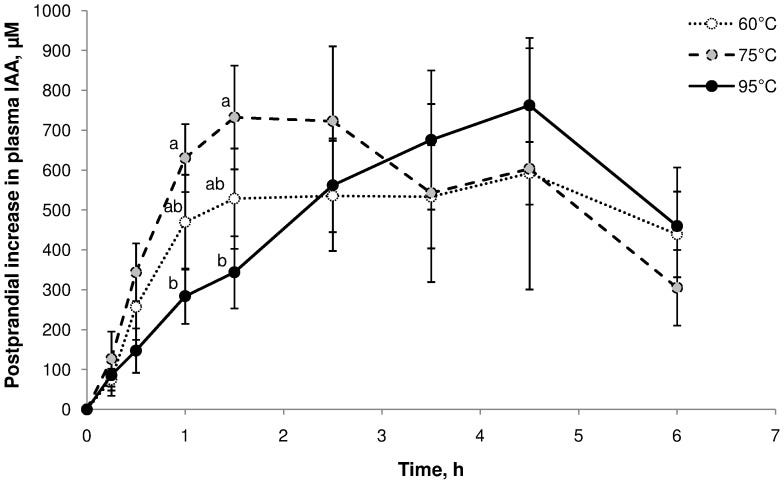

In a 2013 follow-up study by the same team, beef cooked at various temperatures for varying lengths of time was fed to miniature pigs, who were implanted with monitoring devices to obtain more accurate and detailed measurements. The study found that protein digestibility was maximized with cooking temperatures over 75 °C (167 °F), and cooking times between 1.5 and 5 hours. In fact, the single best test bout involved meat cooked at 95 °C (203 °F) for 4.5 hours.

Since these studies used pigs rather than humans as test subjects, it also supports my contention that cooked protein is inherently more digestible than uncooked protein- humans didn’t necessarily need to evolve to rely on fire in order to reap the benefits of cooked food.

In fact surprisingly, a 2015 study on humans by Oberli et al actually found the ideal cooking temperature for humans to be lower than what the Bax studies found for pigs. In this study, meat cooked at 55 °C (131 °F) for five minutes was digested just ever so slightly better than meat cooked at 90 °C (194 °F) for 30 minutes.

For comparison, a rare steak is usually around 130 to 135 °F, medium-rare is 140°, medium is around 155°, medium-well 160°, and well-done steak tops out around 165 °F. So that study compared extremely rare steak to steak that was being cooked way too hot- albeit not for very long at all. The ideal cook temperature is likely somewhere in between, and the ideal cook time is almost certainly more than five minutes, and probably even more than 30 minutes.

Okay, but won't I still get cancer from cooked meat?

The cancer thing is true. Much like a caveman, that statement has a big hairy BUT.

But only if you burn or smoke your meat. Grilling meat over an open flame can form polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a class of chemicals which can damage your DNA. To quote that study: “PAHs have been found to be mutagenic-that is, they cause changes in DNA that may increase the risk of cancer….Significant reductions in the sum of the four PAHs were observed through treatments which removed meat drippings and smoke with alternative grilling apparatus. The sums of 4 PAHs were reduced 48-89% with dripping removed and 41-74% with the smoke removal treatment in grilled pork and beef meats than conventional grilling. We investigated the components of meats drippings. The major constituent of meat dripping was fat. The most important factor contributing to the production of PAHs in grilling was smoke resulting from incomplete combustion of fat dripped onto the fire.”

Another class of carcinogenic chemicals that can form when meat is cooked are called heterocyclic aromatic amines. Whereas PHAs are formed from partially combusted fat, HAAs are formed when the meat itself- that is, the protein portion- gets burnt and crispy. From the abstract of that study: “The bacon clearly contained higher concentrations of HAAs both with longer frying times and at temperatures of 200-220°C rather than 150-170°C, respectively. A similar continuous increase of the concentrations was observed for norharman (5.0-19.9ng/g) and harman (0.3-1.7ng/g). The sensory evaluation, using a hedonic test design for colour and flavour, of the pan-fried bacon slices resulted in a preferred frying time of 5min at 150-170°C. However, some testers clearly preferred crispy and darker bacon slices containing higher HAA concentrations.” (Note: norharman and harman are alternate names for the two HAAs they tested for).

Based on these two studies, the way you cook your meat makes a huge difference. They suggest the following guidelines.

Don’t cook meat over an open flame, or smoke it. Sorry to all the barbecue lovers out there, but cooking with a stove or oven is healthier.

Don’t burn your meat or cook it until it is crispy.

If any fat drips off the meat, remove it. Don’t collect the fat to use for cooking other stuff.

If any part of the meat does get burned, just remove that part. If any smoke is produced during cooking, wipe the meat down to remove smoke residue.

Cook at relatively low temperatures to prevent all of these issues in the first place.

Note that while these studies were done on beef and pork, all meats and eggs contain similar chemicals, and the same guidelines should apply to them too. For eggs, that would mean either cooking eggs at lower temperatures to avoid burning any part of the egg, or boiling eggs inside their shells to protect them from burning and smoke exposure.

Now at this point you may be thinking Wouldn’t I still be better off not eating meat? Not really. The health benefits of vegan diets come from adding fruits and vegetables, not subtracting meat.

There’s virtually no association between unprocessed meat and cancer risk. For processed meat there is an association, but I’ve just showed you how to lower your risk by 80-90%, and the association isn’t that strong to begin with- nowhere near as big as drinking, smoking, being overweight, or being sedentary.

You can have your eggs and eat them too

Based on all the research I’ve cited here, the prescription is pretty clear: eggs and meat should be cooked, but at relatively low temperatures, and never over an open flame. Any fat that does start to melt should be allowed to drain from the meat and thrown away. Cooking them less will reduce protein bioavailability, and cooking them more- with the exception of boiling, which avoids pretty much all of the issues stemming from cooking- will form excess quantities of PHAs and HAAs, which raise your risk of colorectal cancers.

Eggs should either be boiled, or cooked relatively little so they’re still slightly runny. Bacon should be cooked at lower temperatures for about 5 minutes- you should be eating your bacon soft and chewy, not hard and crispy like a damned dirty heathen.

As for steak and other meat dishes, they should be cooked somewhere in the range from rare to medium. Now most Americans say they like their steak medium-rare, but here we have a serious problem: many of you are damned dirty liars. More than a third of all steaks are ordered well-done or medium-well. STOP IT.

As for protein shakes- you’re not Rocky, so leave out the eggs and just use milk and protein powder, mmkay?